|

|

ECE 2100 |

Lab

Work

- Part A: Single-resistor circuit

We will start

out with resistors. We will

discuss more about resistors in

the lecture.

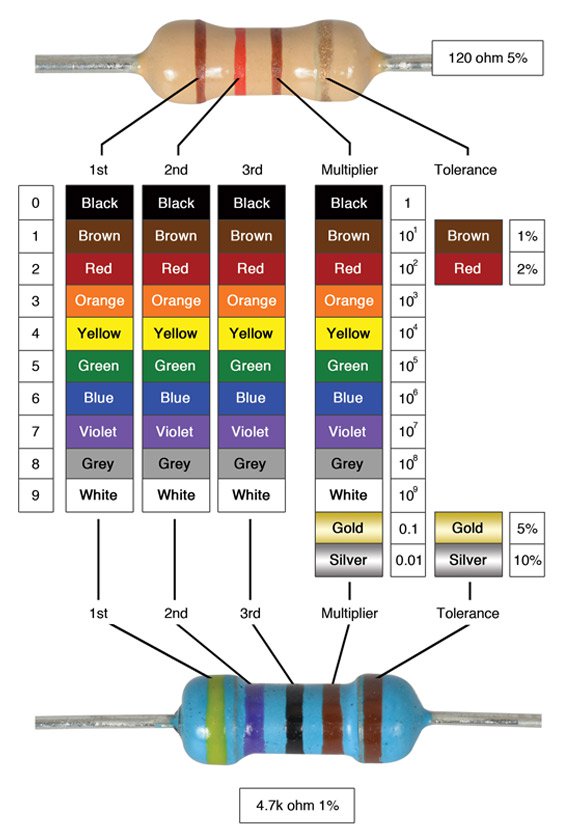

In this entire

course, you will always measure

and report (in your lab reports)

the values of the resistors you

use. One may wonder why we need to

measure a resistor while we can

easily read its value from the

color bands. The answer is that

the color bands only indicate the

resistor nominal value,

not actual value,

because of manufacturing

variation. Given a batch of

resistors, all with the same

nominal values, they can

statistically vary (i. e. differ

from each other) approximately by

as much as the indicated

tolerance, such as 1%, 2%, 5%, or

10%. All

resistors in your electronic kit

are of the 5% or 10% type.

Consider this

example. Suppose we use this

resistor.

Applying 5 V across it, we may

expect a current of:

i = 5V/4.7 kOhm = 1.064 mA.

However, when one measures the

resistor by itself, one finds out

that it is, say 5.1 kOhm instead

of 4.7 kOhm.

Then, the expected current is:

i = 5V/5.1 kOhm = 0.980 mA, not

1.064 mA.

The measured

current should be compared with

the latter figure to determine the

accuracy and precision. Since

an essence of this course

is to learn the good

practice of accurate and

precise experimental

measurements,

it is imperative to do

experimental analysis based on empirical

values - not

nominal (assumed) values of the

circuit elements.

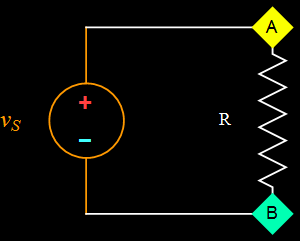

We first

consider the circuit below.

| Schematic |

Breadboard wiring |

Fig. 1.1 |

Fig. 1.2 |

| Figure 1.1 above is

the simplest resistance circuit. Let

R= 100 Ohm or 120 Ohm - your choice

(resistors of these values are in

your electronic kit). The source

voltage is varied from 0 to 5 V. |

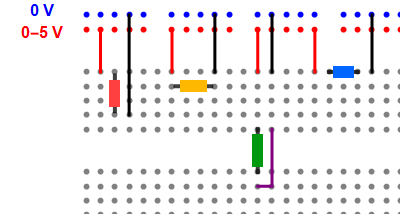

For lab work, we have

to wire the circuit on a breadboard.

Figure 1.2 above shows 4 possible

wiring configurations, the question

is: which of the 4 wiring

configurations represents the

circuit on the left? (select all

that are applied). You can try to answer by reading or watching the videos on page 1 about breadboard, then decide. Or you can just simply build the whole layout as shown on the breadboard and perform measurements to determine which ones are the correct ones. |

| If you build the

whole thing, you will need 4

resistors. Use two 100-Ohm's and two

120-Ohm's resistors from your kit;

it doesn't matter which one is 100

or 120 Ohm, make your choice.

However, as explained above, you

have to report the actual measured

resistance values with the DMM, and

not use the nominal values indicated

by the color bands. |

Work to be

done for Part A:

- build the correct wiring diagrams, or

- build

all 4 diagrams (the whole

layout in Fig. 1.2) and

discover the ones that

don't work. You should be

able to decide which one

is correct by simply

measuring the voltage

across the resistor as you

vary the source voltage

with your BK Precision

power supply.

- explain what's wrong with the

incorrect wiring diagrams in Fig.

1.2. Even if you choose to build

only the correct ones, you still

need to explain the incorrect ones

(why those don't work). Be

detailed and specific.

- select one that works, then measure the

voltage VAB (which is VA-VB) and

current through the resistor for

the following source voltage

values: 1 V, 3 V, 5 V. Plot the

current (x axis) vs. voltage (y

axis).

- when the source voltage is 5V,

use your finger to touch the

resistor and report if you feel

any difference when there is no

current. Explain your experience.

- apply Ohm's

law to determine its resistance,

and compare with the resistance

value you measure with the DMM.

- determine the relative

uncertainty using this formula:

(Rmeasured with V-I - Rmeasured

with DMM)/Rmeasured

with DMM.

- Part B: Single-LED circuit

For the

resistor circuit in Part A above,

if we don't look at the source

voltage indicator, or if the

source is a common battery, we

can't tell if there is a current

flowing through the resistor or

not (unless we have thermal

infrared camera). Here in Part B,

we will use an LED, which emits

light whenever there is a

current flowing through, which

is the phenomenon behind the LED

light bulb.

You will use the LEDs distributed

in class to do Part B. It is

recommended that you go to the

appendix, page i to see

how to do the measurement.

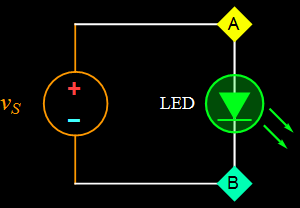

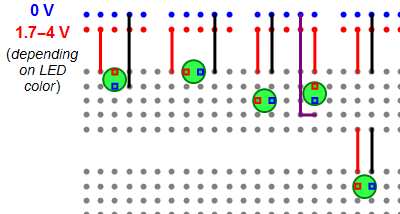

| Schematic | Breadboard wiring |

||||||||||||

Fig. 2.1 |

Fig. 2.2 All LED's should be of the same color (your choice), and the voltage to be applied is shown below.

|

||||||||||||

| Note: LED is a diode,

which allows current to flow only

one way: from the anode (positive

terminal) to the cathode (negative

terminal). |

Figure 2.2

above shows 5 possible LED wiring

configurations. For the LED

(circle), the red square indicates

its anode (positive terminal, long

leg) and the blue, its cathode

(negative terminal, short leg). The question is: which of the 5 LED wiring configurations above will work, i. e. emit light. In fact, if you wire all 5 as shown, you will see that none of the LED will light up, and the power supply will indicate it is short-circuited. By removing just one wire, you will see that the power supply is no longer shorted, and some LED's will emit light. |

Work to be

done for

Part B:

- build only the correct ones; Or

- build the whole layout as shown on the

breadboard (Fig. 2.2); and by trial and

error or use your breadboard knowledge,

remove one wire to determine which wiring

configurations are the correct ones.

- explain why some wiring configurations

work and some don't.

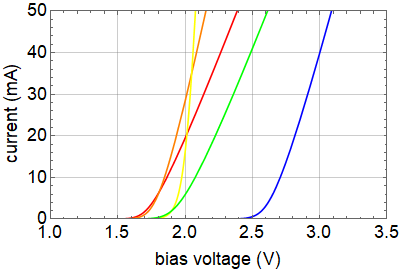

- select one that works, perform an I-V

measurement based on the graph below with

at least six data points (detailed

explanation in the lecture and go to the appendix,

page i for suggestion).

Plot the result. Note: this graph is only

nominal. Actual LED's have significant

deviations from these I-V curves because

of LED material and manufacturing

variations.

These curves were calibrated for a large batch in the past, the new LEDs may have different behavior and these curves should be used only as a guide.

- Part C: Resistor and LED circuit

For the

resistor circuit in Part A above,

if we don't look at the source

voltage indicator, or if the

source is a common battery, we

can't tell if there is a current

flowing through the resistor or

not (unless we have thermal

infrared camera). Here in Part B,

we will use an LED, which emits

light whenever there is a

current flowing through, which

is the phenomenon behind the LED

light bulb.

For the measurement of Part C:

- Select LEDs

of the same color to build

the R-LED circuit that works with

resistor value such that the LED

current is between 15

and

25 mA max (a few mA higher or

lower is OK, don't worry too

much). Use the app (click on links

associated with the gif to

download the cdf version or the Mathematica

notebook icon for .nb file) to

determine the resistor that you

will use. Note that each LED color

may need its own resistance value.

- you can

build only

the one that you know will

work, OR all

four circuits and determine which

one works, which one doesn't.

- explain those that don't work.

- measure the LED current, its

voltage, and the resistor voltage

for the one circuit that works.

- does Ohm's law hold for the

resistor? (as explained in the

lecture, state the % of

measurement uncertainty with

regard to Ohm's law).

Continue to next page (3)